The Nash Bourbaki project is ultimately about figuring out how generative AI can be used to optimize the creative and collaborative experience of writing fiction for the writer. A lot of the chatter around generative AI is more the style of “Look Mom! No hands” … non-creatives trying to impress us by showing off how well they think we can be replaced entirely by machines.

If you ask me, what’s exciting about fiction and art isn’t the structure of the prose, the character development, the perspective or realism. It’s the sense that all those things are instruments of a person trying to connect with you and say something directly to you. Sometimes it’s as simple as “Yes, I agree people smelling each other’s feet is incredibly hot. You are not alone in thinking this.” Sometimes it’s something much more profound. But creative output is only interesting in its ability to make two people feel seen and heard by each other.

Projecting that onto a statistical model is just delusion.

That being said, creatives have a lot of challenges: time management, creative blocks, breaking yourself out of patterns, cliches and tropes. And I’m extremely interested in AI’s ability to optimize human performance by helping people think more creatively, helping reach a flow state quicker and maintain it longer, helping trigger our natural error checking functions more efficiently.

I’ve already written a bit about how Nash Bourbaki uses generative AI to maintain flow state. But a big dissatisfaction I had with that configuration of tools was that left to its own devices (no pun intended!) ChatGPT writes fiction in a terribly cheesy style. Overloaded with cliche—well, frankly that shouldn’t be a surprise. The whole point is to produce words that are statistically likely to follow other words. Obviously that’s going to be full of cliches…

Point is, as useful as it was pairing with even a bad GPT co-author, I wanted to figure out how to get it to mimic my style.

So I asked around. Experimented a bit. Did some programming. Chatted a bit more with other software people. Did some more programming … and then hired a bunch of ghostwriters and fired up ChatGPT again.

Don’t Fine-Tune

My first (incorrect) assumption about this, was that the best way to get a GPT to write in a specific style was to fine-tune it. The results were kind of hilarious. I got very good at watching GPTs having seizures. Which is fun! But not especially productive, so I’ll spare you the technical details and just say: don’t waste your time and money. This is not what fine-tuning is for.

Towards the end of that misadventure I ran into Daniel Whitenack of Prediction Guard at an industry event and asked him: What’s the best way to get GPTs to write in a specific style?

“ICL” he said.

ICL, In-Context Learning, means if you give a GPT a sample text and say write in this style it will write in that style. This works well for technical writing, legal language, academic writing, but is a little difficult with fiction because the consumer GPTs expect to be interacted with through prompts. And prompts work best if they respect certain character limits. A fiction writer’s distinct style is not usually expressed in a sample text of a few paragraphs. Especially when you consider things like the pace and cadence of dialogue.

Embeddings and “Knowledge”

Of course, there are lots of things one could try if you’re going to run a model locally where you have a greater degree of control over the interface and its knowledge base. PrivateGPT and LM Studio are two examples of getting more control and customization without going through the ordeal of necessarily training your own models.

But I made the decision early on that I wanted to do as much as possible with out of the box consumer GPT offerings. Both because it was more convenient, but also because it was just cheaper. Local LLMs still require you to invest in enough RAM and probably also a GPU or two. I wasn’t interested in buying a $2,000 machine just to write trashy stories about vampires and time travel.

Fortunately, ChatGPT’s Custom GPT configurations have an option to upload files to your GPTs as “Knowledge.” I correctly guessed that this was a way of doing embeddings on ChatGPT. Which, in layman’s terms, means ChatGPT is able to look up details about the characters and include them in context when answering prompts.

What I didn’t realize until I tried it out was that this would also inject my writing style into the context of prompts and ChatGPT would start producing text that suddenly seemed a lot closer to the way I wrote.

So if you want a quick and cheap way of getting ChatGPT to write in a style close to your own: create a custom GPT and upload a large writing sample to the knowledge section. I often find it useful to begin prompts with “writing in the style of Nash Bourbaki” to encourage it to use the embeddings effectively, but I noticed the general style improved immediately even without any additional prompt engineering.

Iteration with Ghostwriters

The big test of this custom GPT was never the kind of sentence by sentence co-writing that I’d been playing with before. I was more interested in whether a GPT could rewrite something written by someone else into my style. This would allow multiple authors to collaborate on the same story without driving readers crazy with subtle changes in "voice”, or assigning one character per author in order to hide those changes in voice in characterization.

So I went on Upwork and Fiverr and hired a couple of ghostwriters to produce stories for Reversal’s Alternative Timeline series. ATs worked well because they are designed to be one-shots. Since they are alternative timelines that readers can decide for themselves where/if they fit in the “canon” they don’t have to fit perfectly with the plot lines of the main Reversal story either.

In case you’re interested: there’s apparently a whole community of people who you can pay to write you fanfiction on Fiverr and for my money, the quality of writing from the fanfiction writers was a thousand times better than the freelance fiction writers on Upwork. Go figure.

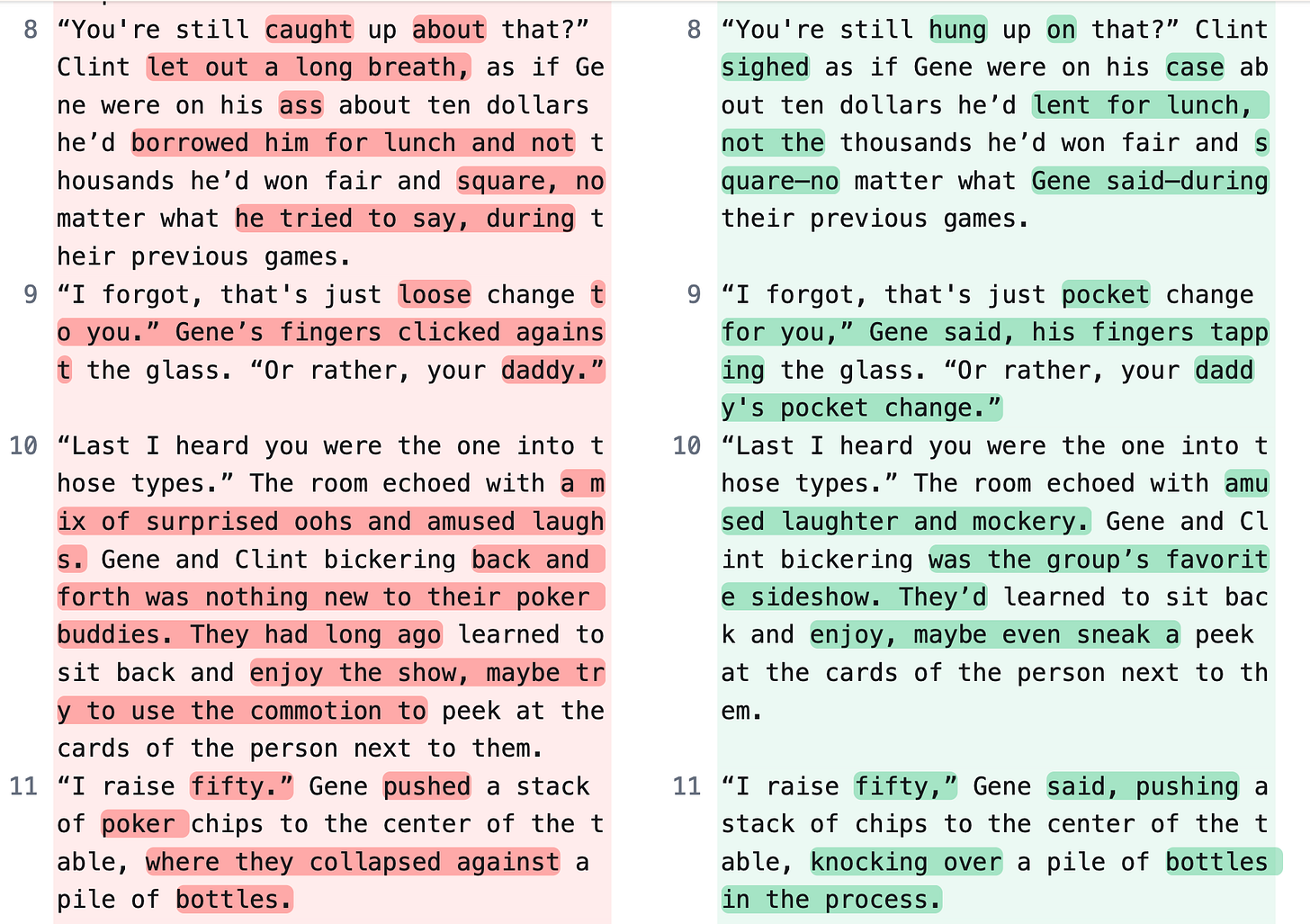

The first submission you all have read as the AT story “Debt Due”. The draft submitted was very good as it was submitted. There were a few factual/characterization errors that were easy for me to fix, some British English that needed to be changed and I tweaked some dialogue here and there.

Then I asked the GPT to rewrite it in my style and the results were actually really interesting.

ChatGPT was able to take a good story and make it sound more like how I write. For a first test, I was pretty happy with the results.

Adding Stylometric Patterns

The next ghostwriter posed a bit more of a challenge, because the next ghostwriter was horrifically bad. Like submitted a draft littered with spelling errors kind of bad. Limp, uninteresting, cliche writing kind of bad. But this was good, strangely, because it presented an opportunity to further refine the GPT’s ability to mimic the Bourbaki style

Here’s a sample of what the ghostwriter submitted:

“The worst part is over,” he said. “All that’s left to do now is wait.”

“I know,” Gene said.

Then Ethan met his eyes. That was a mistake.

Gene’s breath caught in his throat.

The longer he looked, the more he felt like a fly caught in a trap.

After a moment, he had little choice but to look away.

Gene’s eyes wandered the rest of the space.

It was strange how at home he felt in this space. He knew he shouldn’t feel that way, but he couldn’t help himself.

Besides, if it was anyone’s fault, it was Ethan’s.

What else could he expect when he started doing things to make him feel so comfortable here?

It was hard not to feel like Ethan was making room in his life for him.

What else could he call keeping cereal for him?

Gene was sure if he asked about it, Ethan would say he got it for himself. That it was just a coincidence, but Gene wasn’t an idiot. Everytime he came over, there was just as much left as there was the last time he ate any.

He doubted the man would eat something that sweet and processed if he was lost in the middle of the desert and seconds away from starvation.

But it wasn’t just that.

If the only thing he had done was keep a box of cereal around then Gene could probably write that off. He could tell himself it wasn’t about him, but just because he wanted to have something he knew Gene would eat on hand because he drew his blood.

After all, plenty of people got light headed when they had blood drawn and it made sense to take some precautions.

But then he left the door unlocked for him.

(I warned you!!)

Initially the GPT could not do much with this. But I had been meaning to try a technique I read about in a academic paper a few months ago which claimed that the best way to get a GPT to mimic a style was not text samples, but actually a stylometric analysis. Stylometry is more often used in identifying and attributing otherwise anonymous authors, or trying to spot plagiarism, but language models understand these patterns and they can be used to further define an author’s style. Basically how this works is you take a large sample of an author’s work, you tokenize it (OpenAI has a library to help you do this as part of interacting with their API) then you look for repeated patterns. I chose to do parts of speech patterns.

Then I put the analysis in the Instructions section of the GPT configuration:

You are author Nash Bourbaki

Include some shorter sentences with a more stream of consciousness feel. Keep one character's perspective throughout but stay in the third person.

The most common sentence structures Nash Bourbaki uses are:

PRP VBD JJ

examples:

It was nice.

He kissed easy.

PRP VBD RB

examples:

I thought wickedly.

I smiled politely.

PRP VBP DT NN

examples:

We need some mistletoe.

I like this place.

PRP VBP RB

examples:

I laugh nervously.

I smile back.

PRP VBD RB JJ

examples:

It was too much.

It was too late.

PRP VBD DT JJ NN

examples:

It was a scary thing."

It was a rational fear.

PRP VBP JJ

examples:

You sound weird."

"I sleep naked."

PRP VBZ DT NN

examples:

He raises an eyebrow.

It's the plant."

PRP VBZ RB JJ

examples:

It's not important.

He tastes so salty.

PRP VBD IN PRP

examples:

He frowned at me.

I tightened around him.

The most common sentence structure combinations are:

PRP RB VBZ NNP / DT NN

PRP MD RB VB PRP$ NNS / CC NNP MD VB NNP NNS

CC NNP MD VB NNP NNS / PRP MD RB VB PRP$ NNS

PRP MD VB JJ / VBP RB VB

NNP VBD / DT NN IN NN

NN / RB EX VBD DT VBG PRP RB

The more I experiment, the more I see that keeping things simple often leads to much better outcomes. Originally I asked the GPT to categorize the topics that appear in metaphors in Reversal and it put together a great list, but adding that list to the context resulted in revisions that were packed full of awkward policy references in inappropriate places (LOL)

When I cut that out, revisions got much better.

Here’s what the GPT using the new context returned as a revision

"The worst is over," he said, his voice calm. "All that's left now is to wait."

"I know," Gene replied, but he didn't look at him. Not at first.

Then Ethan met his eyes, and that was a mistake. Gene’s breath caught, his chest tightening like a vice. The longer he stared, the more it felt like sinking into quicksand. He needed to break away, but it was impossible, like he was pinned there, helpless.

After what felt like an eternity, he managed to look away. His gaze drifted, latching onto anything else. It was strange how at home he felt in this place. He shouldn’t feel that way—he knew better—but he couldn’t help it. If anything, it was Ethan’s fault. What did he expect when he made it so easy, so comfortable?

It was hard not to think Ethan was making space for him in his life. What else could you call it when a guy started keeping cereal around for you? Sure, if he asked, Ethan would say it was for himself, that it was a coincidence. But Gene wasn’t stupid. Every time he came over, the box was untouched, the same amount left as the last time.

There’s no way Ethan was eating that sugary garbage. Not even if he was starving in the desert.

But it wasn’t just the cereal. Gene could maybe ignore that, write it off as nothing more than Ethan being considerate. But Ethan left the door unlocked for him.

And that was something else entirely.

That’s still not great, but it’s 1,000 times better than the original and there’s a section or two where I feel like the revised text is believably mimicking how I’d write. It got the writing to a place where I could edit it and shape it into something that was at very least acceptable to me. The end result was the AT story Imagined Lives.

Unethical! Immoral! Destructive! (but fun!)

When I did the first write up about using LLMs to improve my creative process, I got a lot of feedback in the vein of “You should be ashamed of yourself!” I can’t imagine this essay is about to win any of those people over. ^O^

The truth is I love writing. I don’t want a machine to do it for me, but sometimes it’s nice to have a machine help me get there faster, or open up possibilities I had not thought of before. People have been experimenting with generative music for decades and no one thinks that’s unethical or immoral … perhaps because composition feels hard to most people … perhaps because music generation did not require the work of others to train the model.

But the fact remains that a lot of professional writers are experimenting with LLMs to make them more creative. This started before the rise of ChatGPT and is probably here to stay:

In 2016, New York Times Fiction Best Seller Robin Sloan wrote about training a language model on a corpus of science fiction short stories [14]. He embedded this model in a text editor such that he could have it complete a sentence when he pressed ‘tab’. His vision for the tool as helper was “less Clippy, more séance”. He imagined that the model would push him to write in an unexpected direction and with fresh language. In 2019, the New York Times profiled Sloan, who has continued working on this project and is using the tool to write his third novel [15].

More recently, critically acclaimed novelist Sigal Samuel wrote about using a language model called GPT-2 [11] to help her write her next novel [13]. She thought that the near-human outputs of language models were ideal for fiction writers because they produced text that was close to, but not quite exactly, human writing. This near-human writing “can startle us into seeing things anew”. She discusses using GPT-2 to finish paragraphs from her previous novels; in one case she writes, “Reading this, I felt strangely moved. The AI had perfectly captured the emotionally and existentially strained tenor of the family’s home.”

How Novelists Use Generative Language Models: An Exploratory User Study